GSD Dexter, 8 weeks

Diagnosis

Description

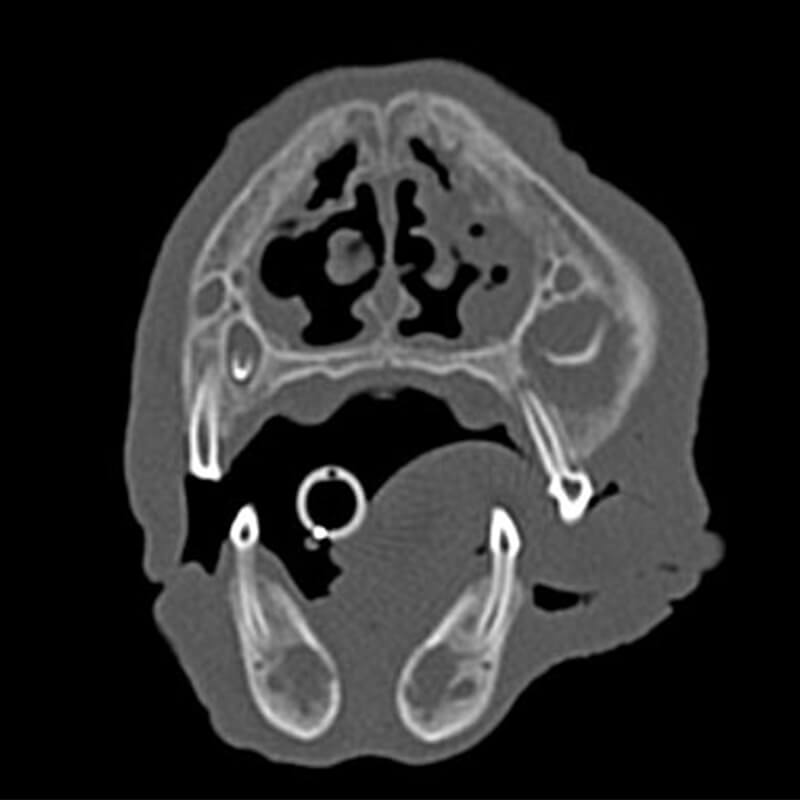

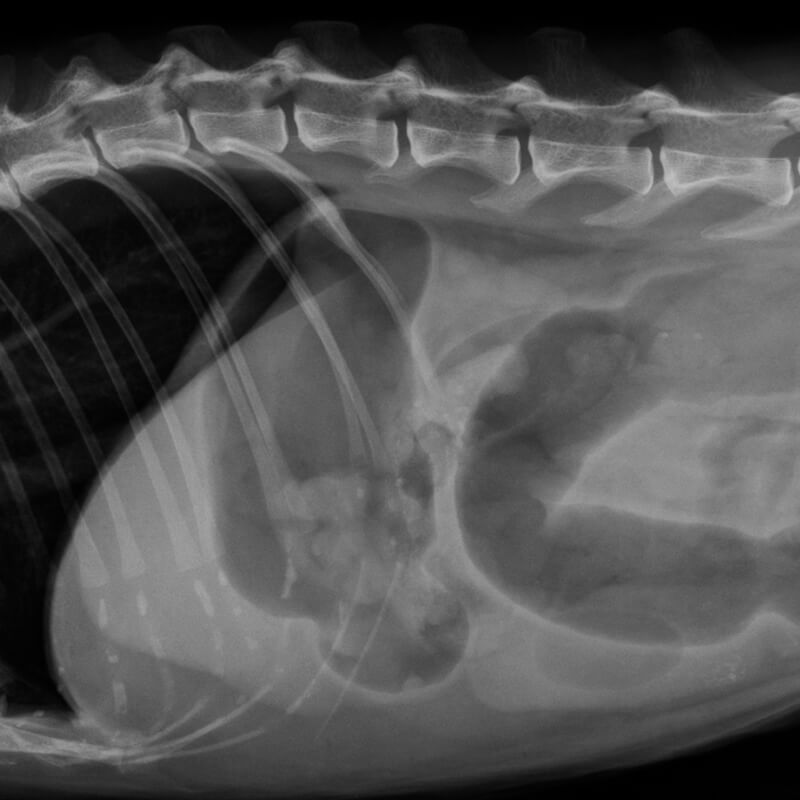

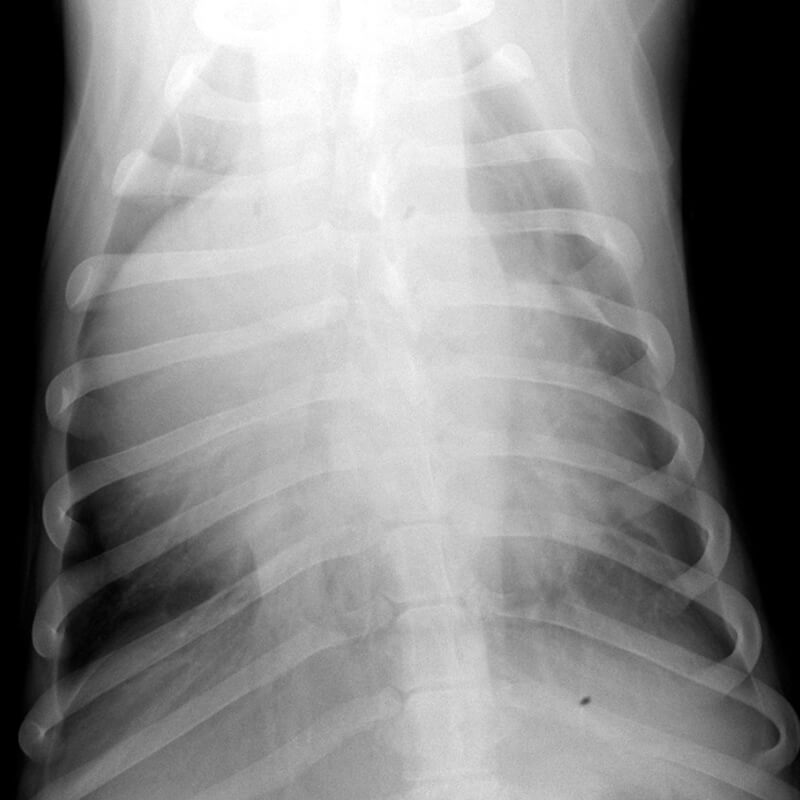

Large expansile, cystic lesions are visible in the right maxilla surrounding the crowns of the unerupted permanent 4th premolar (PM4), as well as of the 1st and 2nd molar (M1 and M2). The oral part of the cortex is partially disrupted at the level of M1 and M2. No connection to the nasal cavity is visible. Large expansile, cystic lesions are also surrounding the unerupted permanent mandibular incisor teeth.

After contrast medium administration moderate, heterogenous contrast uptake is visible within the cystic lesion in the right maxilla and in the incisor part of both mandibles.

A severe reduction in the number of nasal turbinates is present in both nasal cavities. The remaining turbinates appear plump. Material isodense to soft tissue is present between the remaining turbinates. The nasopharyngeal meatus is narrowed and contains a moderate amount of material isodens to soft tissue, which circumferentially occupies approximately 60% of its diameter.

Severe enlargement of the mandibular and the medial retropharyngeal lymph nodes is present bilaterally (left > right).

Radiographic diagnoses

- Expansile, osteolytic bone lesions associated with the crowns of the unerupted permanent teeth (P4, M1 and M2 right maxilla, incisor teeth both mandibles)

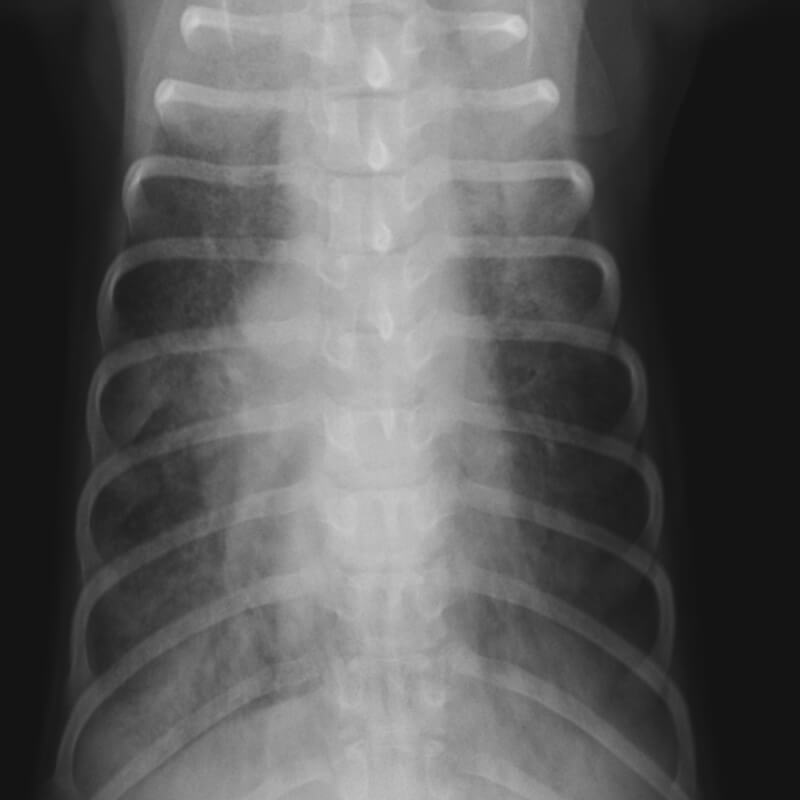

- Bilateral reduction in nasal turbinates

- Soft tissue material between remaining nasal turbinates

- Lympahdenomegaly mandibular and medial retropharyngeal lymphnodes

Discussion

The changes are suggestive of dentigerous cysts. As differential diagnosis odontogenic keratocysts should be considered. However, odontogenic kertocysts are rare in dogs. Differentiation of the various odontogenic cysts required histopathology examination of the wall of the cysts.

The changes in the nasal cavity are suggestive of a congenital hypoplasia of the nasal conchae with secondary bacterial infection. As a differential diagnosis to a simple conchael hypoplasia a ciliary dyskinesia with or with situs inversus (Kartagener Syndrom) should be considered. A chronic bacterial rhinitis with secondary destruction of the nasal conchae is less likely due to the young age of the dog.