French Bulldog, Freya, 10 years

CT dated Mai 2025, with a mass noted at the base of the heart, which was an incidental finding and asymptomatic at the time of imaging.

Diagnosis

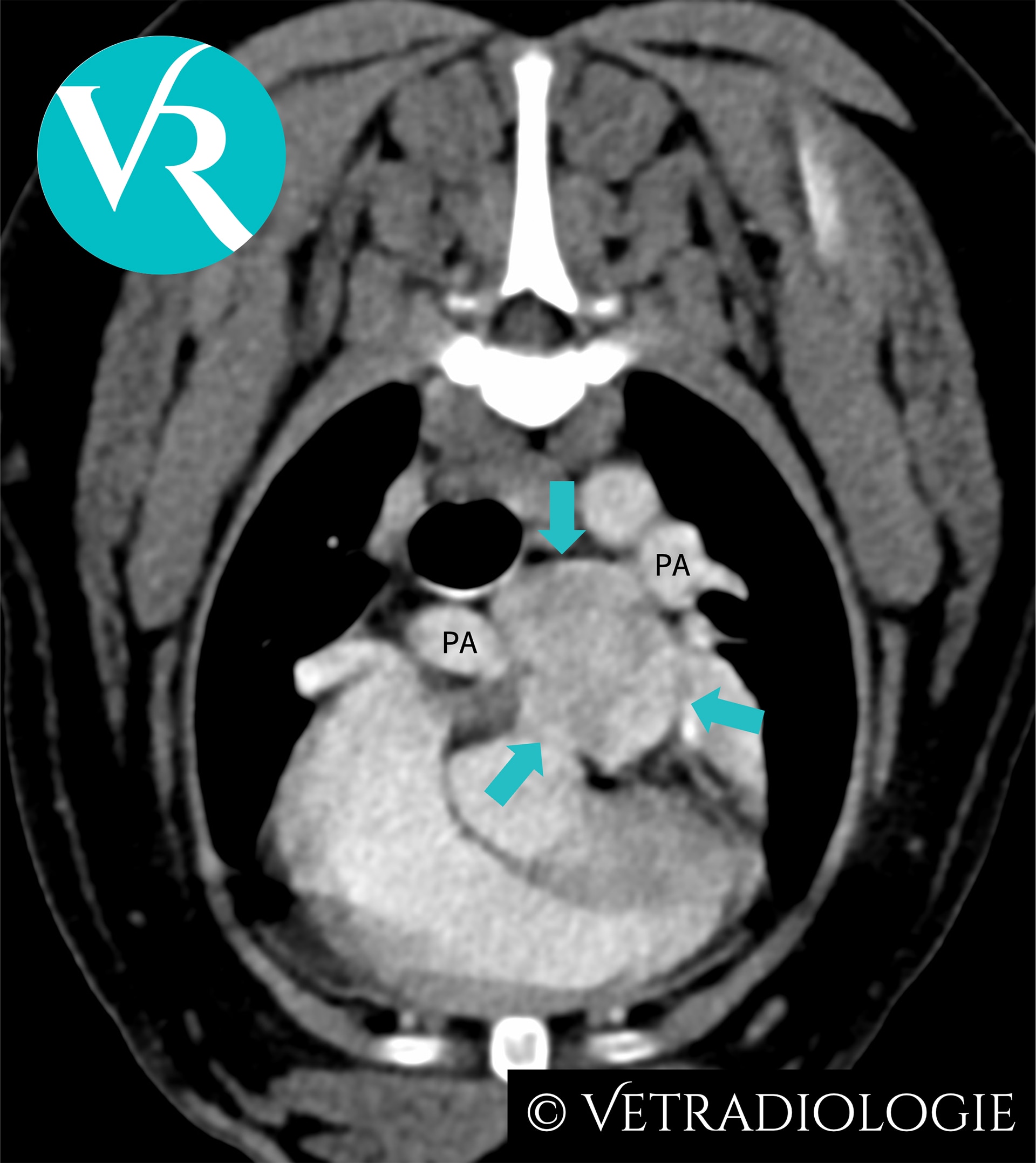

Freya’s CT Study: Note the well circumscribed, ovoid, heterogeneously contrast enhancing soft tissue mass (arrows) at the level of the main pulmonary arterial bifurcation.

CT-Findings

There is a well circumscribed, ovoid, hypervascular soft tissue mass (approximately 2.6cm in maximum diameter) located at the level of the main pulmonary arterial bifurcation, exhibiting heterogeneous contrast enhancement.

CT-Diagnosis

- Heart base tumor

Discussion

Location and morphology are characteristic for a chemodectoma originating from the pulmonary glomus. A chemodectoma is a type of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) arising from chemoreceptor cells at the main pulmonary trunk. These chemoreceptors are organized into glomera and functionally assigned to the paraganglia. Tumors of these circulatory regulatory structures are referred to as chemodectomas or paragangliomas, and are reported more commonly in dogs than in cats.

Chemodectomas are typically benign, non-functional, and exhibit a low metastatic rate, although they may demonstrate locally invasive growth. Due to their slow growth, they frequently remain asymptomatic and—as in Freya—are often incidental findings. However, they may lead to clinical signs such as syncope, exercise intolerance, or sudden cardiac death.

In addition to the pulmonary glomus, chemodectomas/paragangliomas may also arise from other glomera such as from the aortic body glomus at the aortic root or carotid glomus at the bifurcation of the carotid artery.

The chemoreceptors of the glomera respond physiologically to reduced partial oxygen pressure and decreased blood pH. Chronic stimulation due to hypoxemia and respiratory acidosis, such as occurs in the context of the brachycephalic airway syndrome, has been discussed as a possible cause of the increased prevalence of chemodectomas in brachycephalic dogs

References

- Buscaglia NA, Johnson PJ. What Is Your Diagnosis? J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019;254(4):467-469. doi:10.2460/javma.254.4.467.

- Crawford-Jennings MI, Chavez LD, Loessberg ER, Carvallo-Chaigneau FR. Aortic body tumor with intracardiac metastasis in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2025 Mar;37(2):345-348. doi: 10.1177/10406387241304438.

- Fife W, Mattoon J, Drost WT, Groppe D, Wellman M. Imaging features of a presumed carotid body tumor in a dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2003;44(3):322-325. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8261.2003.tb00463.

- Kromhout K, Gielen I, De Cock HE, et al. Magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging of a carotid body tumor in a dog. Acta Vet Scand. 2012;54:24. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-54-24.

- Mai W, Seiler GS, Lindl-Bylicki BJ, et al. CT and MRI features of carotid body paragangliomas in 16 dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2015;56:374-383. doi:10.1111/vru.12251.

- Obradovich JE, Withrow SJ, Powers BE, Walshaw R. Carotid body tumors in the dog. Eleven cases (1978–1988). J Vet Intern Med. 1992;6(2):96-101. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.1992.tb03158.

- Wess G. Kardiale und perikardiale Tumoren. In: Kessler M, Hrsg. Kleintieronkologie. 4., vollständig überarbeitete Auflage. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2022:600f.